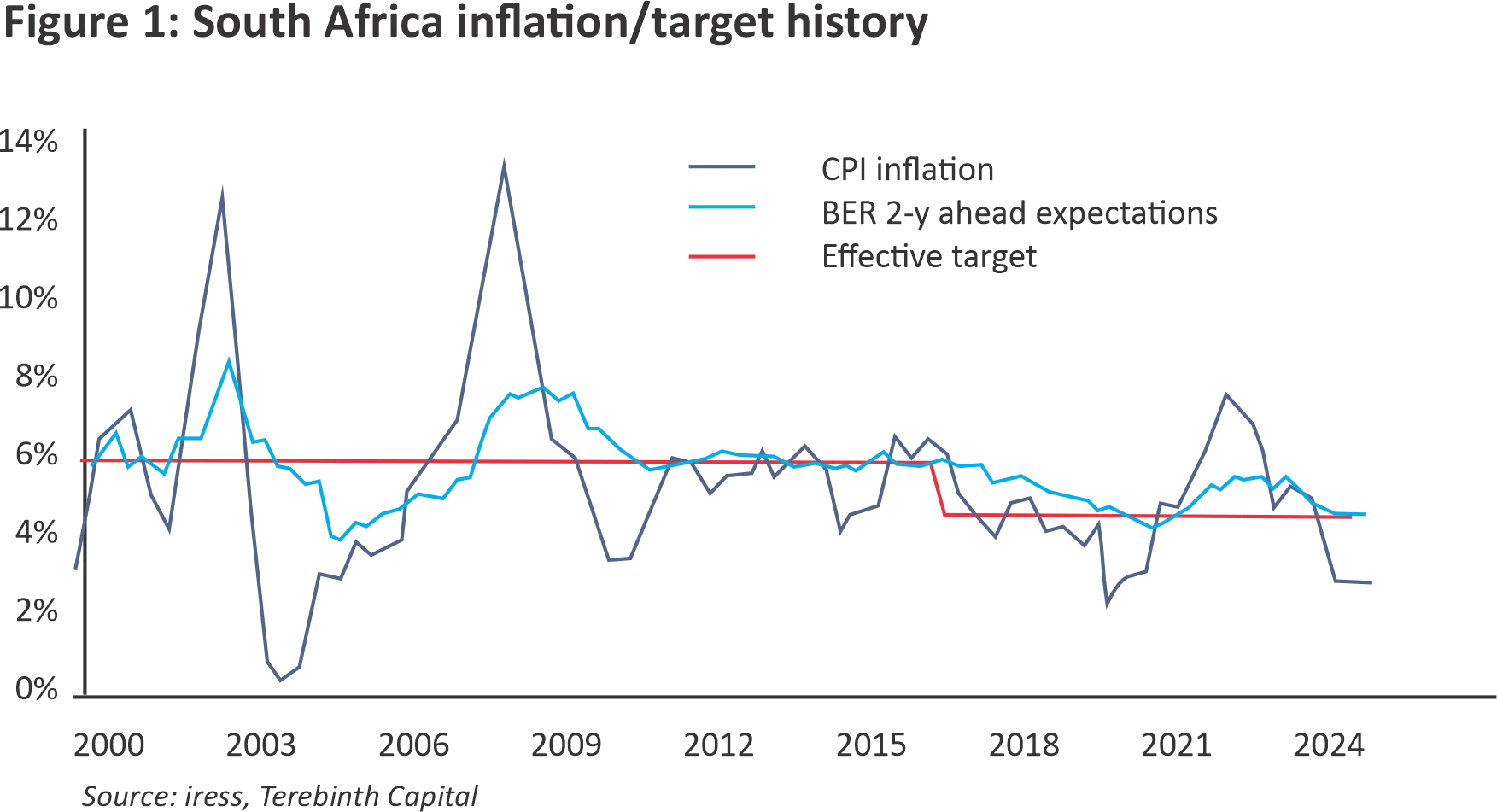

The South African Reserve Bank (SARB) has, under the leadership of Governor Kganyago, significantly enhanced its inflation-targeting credibility over the past decade. With the adoption of an implicit point target of 4.5% in 2017, inflation moderated from 6.0% to 4.0%, with surveyed inflation expectations1 falling from 6.0% to 4.8%. While this was not solely due to the SARB’s actions, the tight monetary policy stance in the face of already constrained GDP growth amid serial attempts at fiscal consolidation ensured that demand-led inflation remained depressed.

South Africa was not spared the widespread supply disruptions in the wake of the Covid pandemic, with inflation surging to almost 8% in 2022. Yet the enhanced credibility of the SARB, alongside vigilant risk management by the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) ensured that inflation expectations were well-behaved, rising to only 5.6%, below the prior effective target of 6.0%.

The steady moderation in inflation over the past two years and notable undershoot in inflation prints relative to the bottom end of the 3% – 6% target range have prompted stronger rhetoric from the SARB that the time has come to explicitly lower the inflation target. The MPC introduced a 3% target projection at its May meeting as part of its scenario analysis.

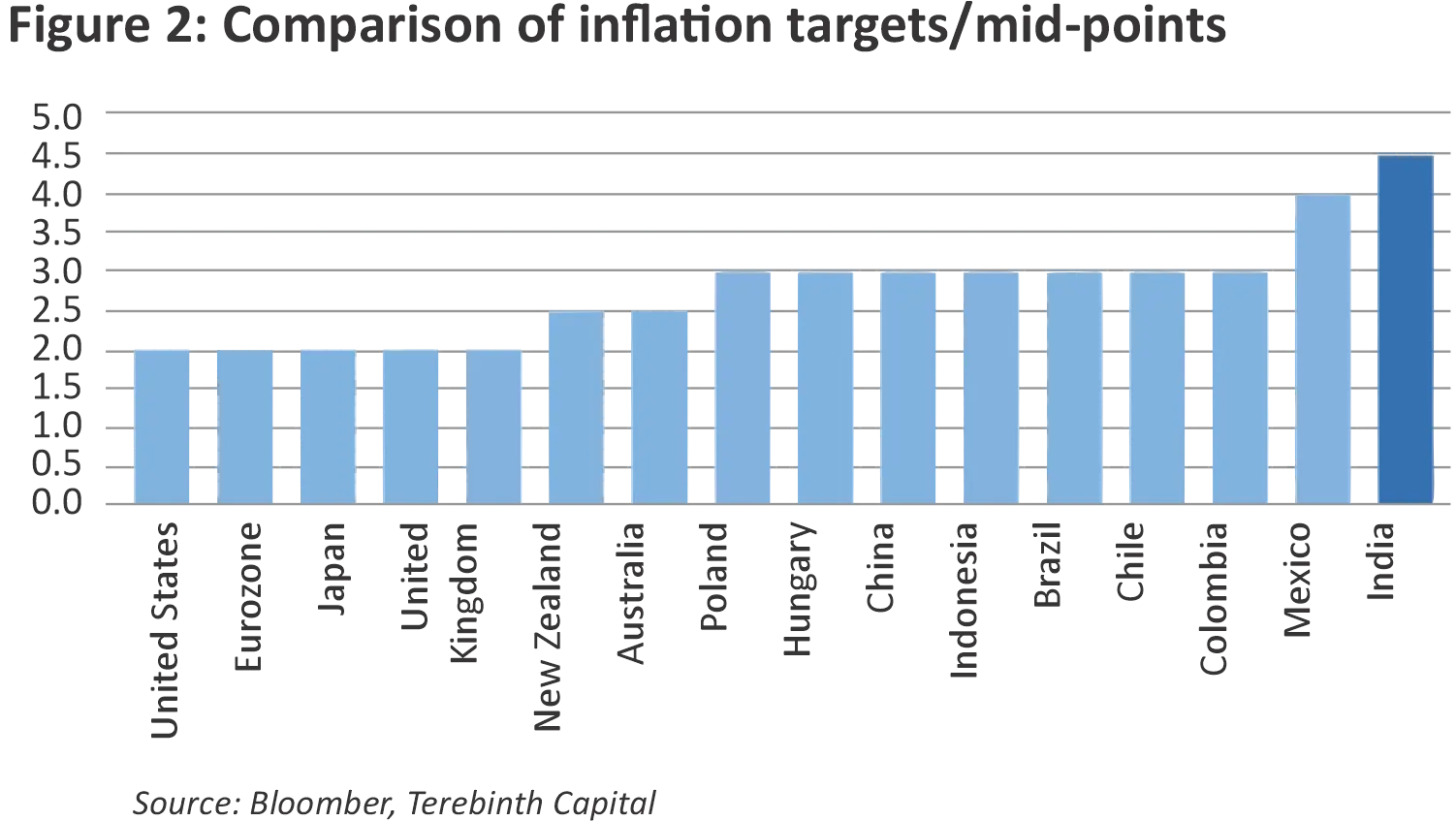

The proposed level (which will most likely take the form of 3.0% ± 1.0% once it is officially confirmed by the Minister of Finance) is informed by the inflation rates and targets of our trading partners. A narrower inflation spread with these counterparts will reduce long term depreciation pressure on the exchange rate, based on the theory of purchasing power parity. This, in turn, will have a positive feedback loop to inflation via contained import prices, facilitating the SARB’s task of fulfilling its mandate.

1 BER 2-years ahead average inflation expectations

Although investors had been anticipating more explicit communication of a lower target, this alternative scenario boosted domestic asset prices, with South African bonds and equities outperforming most of their EM counterparts during June. The questions investors now have to ask are whether this rally has more legs, how durable it will be, and if the SARB’s assessment2 of the low cost to the economy in lowering the target is correct.

Cyclical impact: Bond market partly discounting a lower target

The market expects inflation to average 4.8% over the long term, based on the spread between the 10-year nominal bond yield and the 10-year inflation bond yield – what bond investors refer to as the breakeven inflation rate (BEI). Under a 4.5% inflation target, this implies a 30bp premium, while under a 3.0% target, the risk premium is a wide 180bp.

Since 2009, the average difference between BEI and actual inflation has been 100bp. If we assume the long-run risk premium will change only slowly (being a combination of inflation and fiscal risk) and that inflation continues to oscillate around 3.0%, then BEI could compress to 4.0%. This implies 80bp downside to the nominal 10-year yield, or a new “fair value” close to 9.0%, the level that prevailed from 2016 – 2020.

On this basis there is justification for further cyclical optimism, but the structural spillovers will probably take longer to materialise.

2Loewald, C, Steinbach, R and Rakgalakane, J. 2025. “Less risk and more reward: revising South Africa’s inflation target”. South African Reserve Bank Working Paper Series, WP/25/05.

Structural impact: A series of benign reinforcements

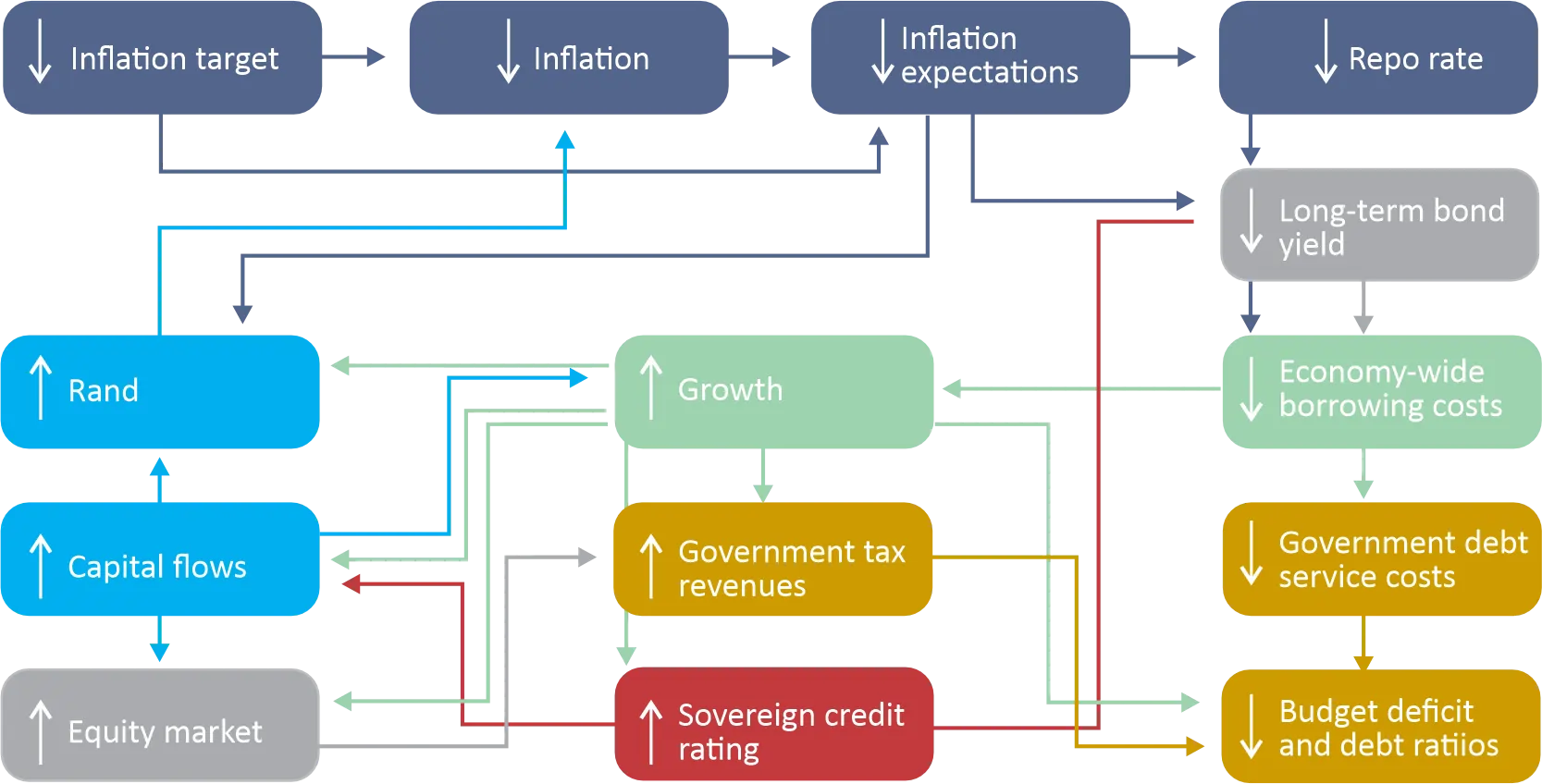

A lower inflation target, combined with SARB credibility, should lead to a decline in inflation expectations and contained inflation outcomes. The SARB MPC will be able to cut the nominal policy rate on a more sustainable basis, which combined with lower inflation expectations, will lead to a fall in the nominal bond yield. A decline in overall borrowing costs for consumers, producers, and the government, will lift GDP growth. Lower government debt service costs and stronger growth will lead to narrower budget deficits and a reversal in the debt-to-GDP ratio.

The main constraints on the sovereign credit rating have been the decline in the GDP per capita and the rapid rise in the debt ratio. As such, improving growth and declining debt would lead to rating upgrades. A stronger sovereign credit rating would encourage inward portfolio and capital flows to support the rand and equity market, as well as raising fixed investment rates to further improve GDP growth. The combination of a structurally lower discount rate (via the bond yield) and stronger productivity growth (higher investment rates) should lead to a structural re-rating in SA equities.

Exchange rate appreciation will dampen import prices and assist in keeping inflation contained to further anchor expectations. A smaller inflation differential with the rest of the world and improving productivity differentials via stronger growth would lead to a more resilient and stable exchange rate. A more stable exchange rate and lower inflation volatility would foster lower interest rate volatility.

Easy, right. Not so fast.

Certain conditions need to be in place for a smooth transition: the SARB retains its independence and credibility, progress on structural reform accelerates to ensure that administered price inflation does not prevent the attainment of the lower target, National Treasury continues with fiscal consolidation, and the exogenous environment is less adversarial. All of these conditions will be heavily influenced by the domestic political economy and global geopolitics.

There may be no reason to doubt the SARB, but the MPC will face numerous exogenous uncertainties, as well as potential domestic political pressure should growth fail to accelerate. Crucially, the survival of the GNU is seen as a necessary condition to keep populism at bay, ensure faster reform, and ongoing fiscal consolidation.

Outside of the political risks, the market may be underappreciating the frictional costs of moving to a lower target.

With regard to equities, a nascent re-rating may be countered by slower earnings growth, as selling prices may be forced to adjust more rapidly than input costs. Moreover, the required tight monetary policy stance in the early phase of the transition is designed to ensure demand-led inflation is suppressed, in a bid to achieve the new lower target. This could limit the growth recovery, with the risk of earnings expectations being missed.

For the bond market, the risk lies in the near-term impact on the fiscus. Pedestrian real growth and persistently low inflation will depress nominal growth, posing downside risk to the National Treasury’s forecast of 6.0% – 6.5%. We estimate that under a 3.0% inflation target, nominal GDP growth will oscillate around 5.0%. If we assume the same tax buoyancy rates as the Budget, then the revenue shortfall averages c. R30bn per year and the nominal GDP shortfall c. R100bn. The net effect is a 0.5 ppt wide budget deficit and a 1.0 ppt higher debt ratio.

According to the SARB, successfully achieving the 3.0% inflation target and altering the funding mix to optimise the cost savings associated with the lower target could lead to a 0.2 ppt decline per year in debt service costs relative to GDP, and a 0.3 ppt increase in annual GDP growth. However, this benefit will come through over time, with the front-loaded pain a cyclical risk for back-loaded gain.

While this first round effect is not alarming, it would require additional spending cuts and/or higher tax rates to ensure the budget metrics are met. Fiscal tightening will be negative for growth, with a negative feedback loop to tax revenues. Based on the 2025 Budget process, it is far from certain that the government has the stomach for even larger spending cuts. Given that we are set to enter the Local Government Election cycle, spending pressures will continue to percolate.

Ramaphoria in 2018 and the GNU in 2024 were not able to lift the structural path for South Africa, but maybe the SARB can.

Time will tell.