It has been almost a decade since the Paris Accords were adopted by over 190 countries. The global agreement to a climate risk transition, to be actioned through various policies, including in some cases, bans on the sales of petrol and diesel fueled vehicles, earmarked the start of the end for industries such as the Platinum Group Metals (PGMs). However, the reality has been different. The rate of decline of vehicles powered by an internal combustion engine (ICE) has been slower than expected as people have opted for hybrid electric cars, which use both battery and ICE powertrains.

The recent growth in hybrid vehicle sales and rollbacks of vehicle emissions targets will have profound implications for electric vehicle (EV) uptake as well as for PGMs, a key component in the catalytic converters used to reduce emissions in ICE and hybrid vehicles.

And as the largest producer and exporter of PGMs, what happens to the sector matters to South Africa. This is more than just an existential ESG matter, but one of grassroots societal importance to a country that is built on mineral wealth and mining. In addition to the more than 181 000 direct jobs within the sector itself, which makes PGMs the biggest employer among South African mining sectors – the broader PGM impact is felt across support industries and within the countless small businesses that service mining towns.

Why is the outlook shifting?

Thus far, the journey towards achieving these targets was zipping along at a steady rate. In the early 2010s, EVs accounted for 0% of total car production and by 2024, they, including hybrid cars, had a penetration rate of just over 20%. Pure battery EVs – which are 100% electric – comprised around 12% while ICE vehicles continued to dominate. Projections were that ICE vehicles would be rapidly put out to pasture as the new technology took over, pushing the demand for PGMs to the side in the process. The automotive industry accounts for over 60% of PGM demand.

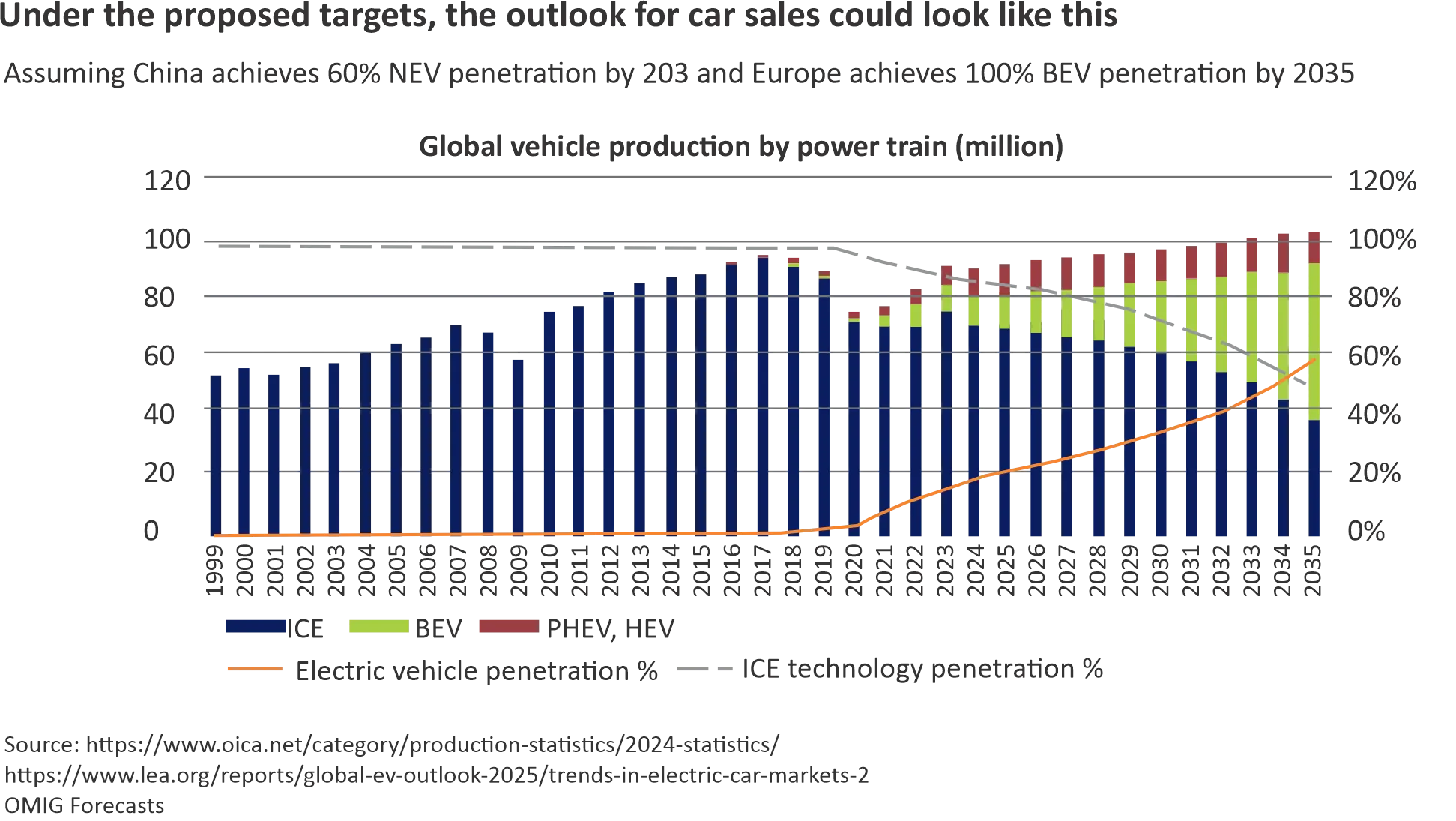

With global car production peaking in 2017, the new growth markets were now emerging nations like China, India, the rest of Asia and Africa. While car sales per working capita in mature markets such as Europe, North America and Japan are slowing down, the emerging markets continue to show an upward trend in car production and sales. An expected trend, as a vehicle remains an aspirational asset in many of these emerging economies. Given the green transition, countries including Canada, the US, Mexico, Japan, the UK, China and continental Europe announced emission reduction commitments and targets which would see electric vehicles leading the way post 2030. Notably, China has a 60% new energy vehicle target by 2030 while Europe has committed to selling only battery electric vehicles from 2035.

As a result of this demand and regulatory push, forecasters anticipated that the penetration J-curve for EVs would keep gaining momentum and accelerate swiftly over the next decade.

However, two factors lay at the heart of these projections. Firstly, that consumers in key markets like China and Europe would make the move from fossil-fuel powered cars to battery EVs and secondly, that automakers would be able to restructure their operations to produce EVs at a scale and price that would entice consumers to make the switch.

If China was to achieve its 60% new energy vehicle penetration rate by 2030, as planned, and Europe saw 100% battery EV penetration by 2035, sometime around 2034 EVs would overtake ICE technology – firmly establishing electric as the dominant technology and, in the process, causing PGM demand to steadily fall by around 5% year-on-year per annum to 2035. With the automotive sector making up about 60% of global PGM demand, this decline would be game-changing.

This was the picture and the inevitable future that was being painted for PGMs. Now, however, this widely held view is being challenged.

Headwinds to EV dominance

While a country like Norway achieved an impressive 96.9% EV market share in January 2025, this came on the back of concerted policy alignment, EV infrastructure development and financial incentives to make it attractive for consumers to buy electric. Import duties were reduced, VAT exemptions were put in place, EV drivers paid reduced toll fees and secured preferential parking options. All palpable incentives to switch. However, Norway is the exception.

Elsewhere, the United Kingdom have pushed back its target date for banning new ICE vehicles from 2030 to 2035, and the European Union (EU) is under pressure to do the same as leading European automakers are being forced to restructure and some cases, close factories.

In the US, President Donald Trump has revoked his predecessor’s target to achieve 50% EV sales by 2030 and has frozen funds reserved for building EV charging stations.

Looking at the two key challenges – affordability and consumer uptake – it’s becoming increasingly evident that, outside of China, EVs are simply too expensive unless, like Norway, financial incentives and subsidies are put in place. In regions like the EU and the US, EVs cost 20%-60% more than the cost of a comparable ICE vehicle.

Governments are unlikely to be happy with Norway’s level of involvement. After all, most had largely delegated responsibility for the EV shift to established car makers. However, this evolution has proved to be a capital intensive and expensive switch, and many of these manufacturers simply don’t have the balance sheets to drive the transition. The likes of Polestar, and EV manufacturer, are actually in negative free cash-flow territory, while other car makers are caught between having to invest in different powertrains to continue manufacturing their bread-and-butter vehicles while simultaneously shifting to hybrids and EVs. With EVs not making the margins, this is impacting the balance sheets of already highly leveraged automakers which, in turn, is adding pressure to this transition.

There are other challenges too, like batteries. While there is a significant global push towards finding more sustainable, long-term solutions in the battery space – including hydrogen, sodium and even nuclear micro-batteries – right now mineral intensive lithium batteries are the main contender. However, even with improved recycling methods that can extract minerals from so-called black mass in an environmentally friendly way, current lithium supply will be unable to support Europe and China’s 2035 targets.

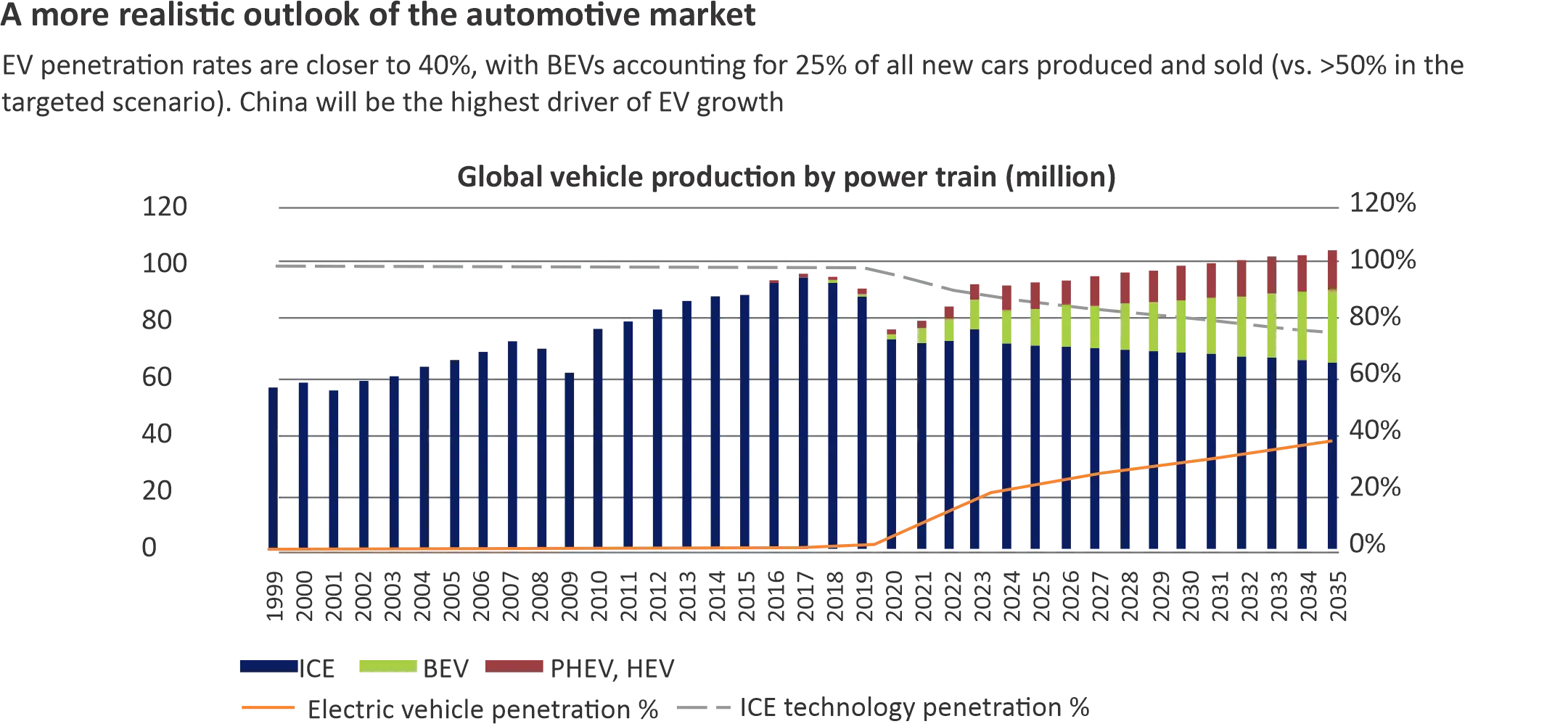

As a result, a more realistic EV outlook is emerging.

Based on our own forecasts and research, we believe a 40% EV penetration rate by 2035 is more realistic than the previous 60% projection. Of this 40%, battery EVs are likely to account for 25%. This growth would be predominantly driven by China, as regions like Europe continue to face their own challenges including charging infrastructure development and battery recycling.

With ICEs still accounting for a large chunk of the global market – alongside hybrid vehicles – there will still be demand for PGMs in this new scenario. In fact, we are likely to see demand for PGMs decline by just 1% year-on-year to 2035, rather than the previously anticipated 5%.

This poses another set of problems. With platinum miners having pulled away from bringing new capacity online, we are facing the possibility of a supply cliff towards the end of the decade, based on our forecast. This is good news for PGM prices but creates another headwind for the emerging EV sector.

For these reasons, we remain bullish on the PGM sector for now.